Role of Taxation:

Provision of goods and services.

To simplify, we can lump all goods and services provided into one of four categories,

based on whether or not the good or service is excludable or rivalrous.

An excludable

good is one such that enjoyment of the good or service can be denied if a

person does not pay to access it. For example, a cookie is excludable while a tree

is not. I can prevent you from enjoying the cookie if I put it behind a viewing

glass and only give it to you to enjoy if you pay me first. Alternatively, even

if I have a tree in my yard, behind my fence, the tree provides shade, oxygen,

and visual benefits to many in the area, and the owner of the tree cannot prevent others from gaining these benefits.

A

rivalrous good is one such that only one person can enjoy the benefit of the

good or service at a time. For example, again, we can use a cookie as an

example of a rivalrous good, while we can use a tree as an example of a non-rivalrous

one. In the case of the cookie, If I eat and enjoy the cookie, you cannot, thus

the benefit of this cookie is only received by the one who gets it.

Alternatively, concerning the tree, this would be non-rivalrous. If you are

enjoying the view of a tree, or its cooling properties, shade, etc. this does

not prevent me or others from similarly enjoying the benefits of the tree.

Typically

speaking, the free market is really good and efficient at providing goods and

services which are both excludable and rivalrous (we call these private goods).

Unfortunately, the free market tends to have a significantly harder time

providing goods which are either non-excludable or non-rivalrous or both. Let’s

take a look at an example of some of these goods.

Club Goods:

Goods

or services which are excludable but non-rivalrous (up to some capacity) are

considered to be club goods. A perfect example of club goods is roads.

Although

we typically do not charge a user fee to utilize a road, it is theoretically simple to

throw up a toll booth or similar technology and prevent access to the road until a user pays. Thus,

although we tend not to exclude them, roads are an excludable good. Similarly,

roads are non-rivalrous (up to some capacity), meaning that typically if I

decide to drive on a road, I am not precluding anyone access to this road. Of

course, there is a point where the roadway becomes congested (traffic) and roads

switch from being a club good to being a private good.

The

problem is that to efficiently provide a club good, we need to price

it accordingly. That is, a club good should have a zero-user fee when there is no

congestion, however when we move to a congested state, then the good has a

price to reflect the cost that one person inflicts on another by

denying them access.

If roadways (or other infrastructure such as sewer, water, bridges, tunnels, pathways,

etc.) are provided by the private sector, then typically the focus of the

provision of these services is around areas that face congestion. That is, the

private sector would have an incentive to under-invest in these goods and

services to have congestion to be able to charge an effective

(profitable) price for them.

Thus

we, as a society, have typically decided that due to the social benefits that

are provided by these goods and services, we should have government over

private enterprise to provide this good or service and typically allow them to

be provided for zero user cost and instead finance the use of the good through

general tax revenue.

The

problem that this then creates of course is that individuals have no incentive

not to overutilize the resource (because it is free to use) thus creating

rivalrous situations (such as traffic jams).

Common Resource Goods:

In this

case, we are not typically talking about the provision of a good or service,

but rather the managing of an existing (typically natural) good or service. The

solution to preventing a collapse of the resource itself is through the use of legislation

and imposing a tax on the utilization of this good or service through the

form of a user fee. This is often seen as a permitting fee, stumpage fee, or

usage fee. The purpose of such fees is to limit consumption of the good or

service to prevent its collapse. This is often the key argument for forestry

bylaws, resource royalties, and water fees. That is, these fees are not being

collected to provide a good or service, but rather being charged to limit the

consumption of a good or service, and thus promote the effective and sustainable

management of that good or service.

Public Goods.

The

final type of good or service to look at for public provision is a public good.

This is a type of good that is both non-rivalrous and non-excludable. The

classic example of a public good is a park or large green space.

Due to

the nature of public goods, the private market tends to significantly under-provide them. For example, let's look at the ability of individuals to come

together to fund and build a new park.

Suppose

that there is an orphaned lot in your neighbourhood, and you and all your

neighbours agree that this would be a great spot for a park, some green space,

a few trees for shade and maybe even a small play structure. To get

this to happen the neighbourhood needs to solicit donations to fund the

construction of this. While scenarios like this do happen, and we are capable

of building parks in this fashion – what is the difficulty we run up against?

The issue is that everyone agrees they’d benefit from the park being built.

This means that they’d benefit irrespective of whether they donate money or not,

as long as it is built. From an individual view then, each person would be best

off if they don’t donate, or only donate very little, while their neighbour donates more, allowing the park to

be built. The issue of course is that everyone hopes that their neighbour

donates so that they don’t have to and the result is either that a) the park

does not get built or is underbuilt or b) a significant amount of time and resources have to go

into raising funds. The result of either of these scenarios is that private

individuals are generally unable to provide a satisfactory amount of public

goods.

The

solution then is for the government to recognize the need and social benefit

received by these public goods and then provide them through general taxation

revenue. Essentially forcing each member

of society to contribute a little to a project to create a public good

that nearly all will enjoy, thus increasing the social welfare as a whole.

A final note on public provision of private goods:

There

of course are certain private goods (excludable and rivalrous) that we as a

society have decided to provide through taxation rather than allowing the free

market to provide and charge. Some examples of these are policing, fire

protection, education and health care.

In each

of the above cases, the service provided is rivalrous. If you need a police

officer, firefighter or health care professional you are preventing someone

else from accessing their service. While similarly these services could easily

be excluded. You don’t get to utilize the service unless you have paid for it

first, or alternatively, will be billed after the fact.

Even though these (and other) goods and services are technically private and

thus could be provided more efficiently through the private market, we have

collectively decided that the social and equity impacts of having these

provided through the public realm outweigh the potential inefficiencies that

arise through its public provision.

Role of Taxes continued:

This

then brings us back to completing our conversation around the role of taxes. First

and foremost the role of taxes is to collect general revenues to then be

able to provide Club, Public and selected private goods to the residents at

zero or low user cost. This is the provision of roadways, bridges, tunnels,

bike lanes, schools, hospitals, parks, green spaces, rec centres, libraries,

etc. This ensures in the case of club and public goods that enough of the good

or service is being provided for the benefit of society, or in the case of a

publicly provided private good, that we have equitable access to the good or

service irrespective of ability to pay (IE. Schools, hospitals, etc.).

The

second role of taxes is to encourage pro-social behaviour. This is best seen in

the case of common resource goods. As history has shown time and time again the zero cost to utilize certain resources results in the overuse and exhaustion

of the resource. Just look at the Atlantic fisheries, many forests in eastern

Canada and Europe, and our current use of a clean environment. In this case, the role of

the government is to appropriately price the good or service to

prevent its exhaustion and to ensure that it can be appropriately managed sustainably. Thus, the role of taxation is to prevent or limit consumption,

and then to utilize the revenues raised to either subsidize non-exhaustive

alternatives or to fund the costs of managing the resource at risk. A great

modern example of this would be the introduction and implementation of the

carbon tax which both discourages consumption of carbon-intensive resources,

funds the management of climate-sensitive areas and subsidizes alternative

forms of non-exhaustive (“green”) goods.

High cost of Low taxes:

With

the basis of why the government collects taxes and provides the above-mentioned

goods and services, what happens if the government fails to collect sufficient

tax revenues? While hardly an exhaustive list, there are a few potential

outcomes which have varying levels of social, and fiscal implications. Keep in

mind, while I have said the following list is nowhere near exhaustive, it is

also not mutually exclusive, many of these outcomes likely take place in mixed

scenarios.

Postponing of costs:

Let’s

start with the most straightforward of scenarios. To keep taxes low

today, a government decides to postpone known costs. That is, they continue to

provide current goods and services as listed above, but they neglect the

amortized maintenance and replacement of these assets that will have to be

funded in the future. For example, let's suppose that we could forecast that a

new police station is needed for $500,000 in ten years. We could

explore a few different scenarios.

a) 1) Put aside $X each budget cycle to save for this

project.

b) 2) Keep taxes low today and wait till some future

time to start saving.

c)

3) Wait till the end and debt finance the whole

thing.

Let’s explore what this looks

like in each scenario, if we presume a 5% prevailing interest rate, and

presume we could get this same rate on our savings and borrowing, we face the

following decisions based on when we start financing:

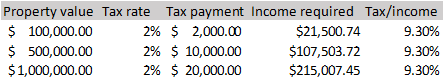

That is, as we can plainly see, every

choice to keep taxes low today, by not putting money aside for known costs,

results in a larger tax lift needed tomorrow, Further, this decision puts a

higher burden on the taxpayer as each year postponed is a year where

compound interest cannot be earned.

While the final option, to

borrow, results in an annual tax lift between beginning to save in years three

and five, the resulting burden to the taxpayer is the highest of all. If we

make a further presumption, we can see the impact of each as a percentage

increase to the budget. To keep things as realistic as possible let’s presume

that we began with a million-dollar budget that, by default, will have to

increase at 3% a year to cover inflationary and growth pressures. That being

the case we can witness the resulting required tax lift (above the 3%) to finance this replacement in each case:

Again,

we can see in the final row added, that each year of postponement results in a

drastic increase to the tax lift needed to meet this future

obligation.

Moral

of this story? You can kick the can down the road to keep low tax rates for a

while, but eventually, all bills come due! Even if you decide to leave it and just borrow

in the future, the tax burden is significantly higher than had you simply made

the tough choice up front.

Cutting services:

One of

the other options that governments have to keep the taxes lower, would be to

cut services. Keep in mind the services provided are typically done so as they satisfy

a need that is unmet by the private market due to the nature of non-rivalrous

and non-excludable goods.

The

choice to cut services is fine. It is ultimately society’s role to determine

which services are desired and which are not. As we progress, grow and change, our demands and desires for services also grow and change. Thus, over time

certain services that were once provided by the government may no longer be

beneficial, while others that were never on the radar are now pressing.

The

issue with cutting services is ultimately similar to that of postponing costs.

If you cut funding for services, despite a growing population, you are asking

those who work in that field to do more with less. While initially this can be

done for a time, it ultimately leads to staff burnout, fatigue, and inability

to deliver on the mandate given.

The

result is often a failure or a near collapse of the system. We can see this

currently in the aftermath of decades of service level cuts across much of the

public service, but arguably most painfully felt in the fields of education and

healthcare.

Suppose that budgets were cut by

a half percent based on the argument that this would improve efficiency. While this might not seem like a

large impact, after 5 years, an increase of 2.54% would be needed to return to

the original funding amount, and after 10 years an increase of 5.14% would be

needed. That is, while you might be able to cut taxes to put the squeeze on a

certain department, the continued squeeze on a department requires a large

single-period increase to return to baseline service levels in the

case that this ‘efficiency’ is not found.

The tangential case of cutting

services is not allowing services to expand. Suppose that the population and

service demanded is increasing by a half percent a year. Rather than meeting

this increased demand with increased staffing and resourcing each year, you

would be required to make a 2.54% increase in 5 years and a 5.14% increase in 10

years simply to catch up to the underinvestment in staff and resourcing.

Again, the resulting message is

either a small pain today or a large pain tomorrow if you decide to kick the

can down the road.

Charging user fees:

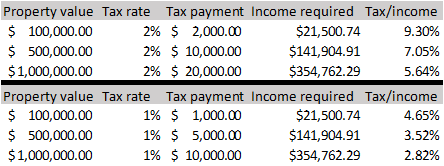

One way

to lower the general taxation rate is to shift some of the burden of provision

of services from being funded by general tax revenue, towards being funded

either entirely or partly through user fees. The more things you can shift

towards user fees the less you can charge in general taxes, but the more the

households that utilize this service tend to pay as a proportion of their incomes.

The charging of user fees is an

interesting economic case. On the one hand, if you can identify the individual

who will benefit from the good or service, then they ought to pay for access to

this benefit. Think of rec-centres and pools in this case. On the other hand,

many of the goods and services provided by the government are provided due to the

social benefit that they provide, and the charging of user fees acts as an

additional per unit tax which typically adds to the regressivity of a tax system.

There

are many services provided by the government such that it is easily identifiable as

to who is benefiting and thus able to charge them for access. From fire,

police, education, public transportation infrastructure, recreation, sewer,

garbage, water, I could go on. It is ultimately a policy choice whether or not

to charge for any of these services through user fees.

If the

choice is made to not charge for these services, then we will tend towards over-utilizing, exhausting, or operating these resources over capacity – think of

traffic on the highway partially due to no user fee, or wait times in the ER

due to similar reasons.

Alternatively,

if the decision is made to charge for these services through a user fee, then

the user fee in essence acts as a tax to access. As this tax is a flat rate

($10 to drop into the pool for example) then this user fee by definition would

be regressive as a $10 fee is a larger proportion of income to someone who makes $500 a

week versus someone who makes $1000 a week.

Further,

as the user fee is ultimately an optional tax (only pay it if you access it) the

resulting social impacts are that those with lower incomes will tend to

self-select out of these services, some of which are argued as vital for health

and well-being.

Thus,

the choice to shift the tax burden from general tax revenue to user fees has

the potential of adding to the regressive nature of taxation, predominately

benefiting the higher-income earners while negatively affecting those who earn less.

Privatization of services:

To finish

off this non-exhaustive list, let's look at the option of privatizing services. The

idea of this was largely popularized with the rise of neo-liberalism and the move

towards privatization of public assets seen worldwide but predominately

championed by Margaret Thatcher in the UK and Ronald Reagan in the US.

The basic idea is that the

private sector is more efficient than the public sector, thus if we privatize certain

public services, these services will be able to be provided more cost-effectively.

While it may be true that the

private sector can be more efficient, this is based on the assumption that the

private sector is operating with high levels of competition. Many goods and

services provided by governments are essentially monopolistic goods. Thus,

the privatization of these lines of business provides a one-time boost to the

budget as those assets are liquidated, but often results in long-term reduction

in service levels and cost increases in line or greater than what may have been expected

had it been kept in the public sphere.

Of course, this is not always the

case – there are situations like the privatization of insurance in Alberta or

the privatization of telecommunication where due to technological advancements

competition was able to exist, thus driving a more efficient outcome than

the government service. Unfortunately, however, more cases of privatization

result in the privatization of a monopoly provider which we will continue to

explore in this case.

Let’s presume that to keep

taxes low today, the decision is made to privatize a certain line of public

service that had a budget cost of $100,000. Again, if we keep things simple, for this to make sense the contracted provision of this service must be

either the same or less than the current public provision cost. Let’s presume that

the contractor can initially provide this service for $90,000 an instant savings

of $10,000 as well as the positive cash flow from the sale of assets associated

with this business line. Looks like a win.

Let’s look at some of the

distributional effects. First, when this was provided publicly, it was

typically provided by higher wage unionized workers, meaning that a larger

proportion of this cost was going towards the labour force, those actually

doing the work as well as the managers. When this is privatized and the service is now provided at a lower cost, the new

entrepreneur has two options to turn a profit, either cut wages or

cut service levels – typically both.

The result of the cutting of

wages is a transfer of wealth from a distributed level between several workers

into a concentrated level in the hands of the owner(s). Further, if possible,

the reduction of service levels results in a lower provision per dollar spent

by the public, thus society as a whole tends to lose while the few owners are

the ones that tend to gain the most from the provision of a previously public

service through privatization to a monopoly.

The outcome described above has

been witnessed and played out time and time again. Without going into a full history

of these events a brief look at the privatization of highway maintenance in

Ontario, the privatization of prisons, the privatization of air ambulances and

more highlight the frequent failures of privatization to monopoly providers.

The long-term effects of privatizing

to a monopoly provider can be worse, in many ways binding governments to perpetual high-cost, low-service contracts. Many of these lines of business are

monopolistic due to the extremely high capital cost of providing the service. As

a result, there are often very few if any competing bids at each contract

renewal. When this happens the monopolist provider knows that the government only

has two options, accept their bid to provide the service or take the service

back in-house.

This creates a moral hazard

problem as the monopolist provider knows the huge capital cost that the

government would have to face to bring this back in-house, and thus

knows that the government cannot likely repatriate the service.

Thus, knowing this, the monopolist provider has the majority of the power in the

contract negotiation, able to push the terms of the contract renewal to be

increasingly in their favour over the public or taxpayers’ favour, thus

resulting in even higher costs to the public, higher levels of wealth

concentration in the hands of the few owner(s) and lower levels of service.

There is significantly more

research that exists on this topic, a fairly straightforward, non-technical,

analysis of the failure of privatization can be found here,

or an even easier read is this economist article that can be found here.

Conclusion and summary

Throughout this post, I have aimed to justify why the government has a role in providing goods and services and how the government can attempt to provide these services

equitably (trying to promote vertical and horizontal equity of

taxation). Further, I discussed the problems due to pandering to an electorate by

artificially keeping taxes low by postponing costs, cutting services, shifting

costs from taxation to user fees, or privatizing these services altogether.

While

it is the policymaker's prerogative to undertake any of the above actions to

provide a momentary reprieve in general taxation, the policymaker needs to

recognize that any reprieve today will result in a higher cost tomorrow as

demonstrated in each of the above cases.

Thus,

the primary role of the policy maker is to determine which services are to be the

responsibility of their government and ensure through proper governance, oversight of management, and planning that these services are provided in the most effective way to promote the highest possible social benefit.

Unless a given good or service is now obsolete or is not capable of being provided through a truly competitive market, then any decision to postpone, or cut funding to an effective service today, will result in a higher cost tomorrow, thus we have our high cost of low taxes.

As always should you have any questions, thoughts or comments, please feel free to reach out or comment below!