As we are approaching the municipal budget season with some local governments having already launched their draft budget, and others on the eve of doing so, I felt it would be worthwhile to spend a bit of time to speak about some of the theories around taxation and fiscal policy. To be clear, this is primarily aimed towards economics and public administration students or anyone who may have an interest in public and fiscal policy. I am aiming to educate on many common terms used in fiscal policy, and while I make some comments evaluating policy decisions, these are included as a learning aid to provide context to the discussion.

I Intend, over the coming weeks, to launch a

series of blog posts on this topic. However, in this post I want to spend some

time exploring the ability to pay, progressive vs flat vs regressive taxation, and tax

equity, and then wrap up by looking at how property taxes fit into these

definitions.

Ability to Pay

First, we need to define and look at ability to

pay. While, here, I will explore the full range of ability to pay, it will be

important to recognize that the rest of this conversation focuses only on Income,

not ability to pay.

To think about ability to pay we need to define

the difference between flow and stock variables and how they relate to income

and wealth.

The classic example used is that of a bathtub

or a sink. The tap that adds water is the positive flow of water into the tub,

while the drain that, drains, water is the negative flow out of the tub. The amount

in the tub is the stock of water.

In this same way, we can view an individual’s ability

to pay. One’s income is the flow of money in, and one’s expenses are the flow of

money out. Beyond this, we also have one’s savings, which is their wealth.

All else equal, if Income is greater than

expenses, then one’s wealth is growing, that is the bathtub is filling. If one’s

expenses are greater than income, then one’s wealth is shrinking, that is the

bathtub is draining. Of course, we have the added complexity with money that

one’s wealth is capable of growing or shrinking on its own through appreciation

or depreciation or through earning income itself through interest or dividend

payments.

While ultimately one’s ability to pay is

determined through their total ability to pay from either income or wealth,

from a taxation perspective the focus is primarily (and historically) based on

one’s ability to pay purely from income. That is, the stock of wealth is

predominately ignored, and the focus of the discussion around taxation regimes

tends to focus on the flow of income.

Focusing then, just on income, let’s move on to

define some commonly used terms that define different taxation structures.

Flat Taxes

We will begin this by looking at

what is arguably the simplest form of taxation, which is a flat tax.

In this case, everyone pays a

constant proportion of their income in taxation, say 10%. Thus, whether you earn $10,000 or $50,000 or

$100,000 a year all will pay 10% of their income in taxes. Of important note,

while all three of these listed incomes pay the same proportion, the amount of

taxes they pay is clearly increasing. This can be seen in the table below:

Progressive Taxes

Progressive taxation is a case where higher income

earners pay higher proportions of their income in taxation.

It

is difficult to have a conversation around progressive taxation if one does not

fully comprehend the notion of a marginal tax rate. As a discussion of marginal

tax rates would be a post on its own, I would recommend that anyone who does

not fully understand marginal tax rates take a moment and look this up to obtain

a cursory understanding.

If we were to continue to utilize the same incomes

as introduced above, under a progressive taxation system we might expect each

of the above income earners to pay an average marginal tax rate of 0%, 10%, and

20% respectively.

That is the lowest income earner may not even

pay taxes, and as one’s income increases, so does the proportion of the tax

that they pay. The amount of taxes paid under the above-imagined progressive

system can be visualized in the table below:

Regressive Taxes

Finally, let’s explore a

regressive taxation scheme. A regressive scheme is really just the opposite of

a progressive one. That is in this scenario an individual would pay a lower

proportion of their income towards taxation as their income rises. An example

of this would be a scenario such that as one’s income rises; they are capable

of hiring a tax professional which allows them to take advantage of tax loopholes

to lower their overall rate of taxation. The result of such a taxation scheme

can be visualized in the table below:

It is important to note that the

value of the taxation, in this case, is still increasing as income increases.

Those earning $100,000 are still paying more in taxes than a person earning

$10,000. However, the proportion of their income that is going towards taxes is

shrinking. That is, the value of the tax payment does not need to be decreasing

for a system to be regressive.

Tax Equity

Above we introduced three

different taxation regimes, flat, progressive and regressive with respect to

income. Next, in this section, we will introduce two ideals, which when

utilized, help create a taxation system that is typically understood to be fair

and just. These are the ideals of vertical and horizontal equity.

Vertical Equity

Vertical equity is actually the

foundation for a progressive taxation structure. A taxation system would have

greater levels of vertical equity if those with greater ability, pay a higher

proportion of their income towards taxation. While this might be intuitively

believed by some, it is of course challenged by others. So, let’s take a moment

and look at a few arguments as to why a taxation system that is preferred from

an equity viewpoint.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

While I have not found any actual reference

to this. The concept of vertical equity was explained to me years ago along the

lines of Maslow’s Hierarchy of needs.

We have as our base physiological needs such as

water, food, shelter, and clothing. If our income is such that we can only provide

these needs for ourselves we have very little if any capacity to support society

through taxation. Thus, the idea is that at these income levels, you ideally

would not be subject to taxation. Without getting into the policy discussion of

whether or not this is an adequate amount, this is the rationale that your first

$15,000 (approx.) of income is tax-free – this provides one with the ability to meet

their own base needs before they start paying into services that help meet collective

needs.

As we move up Maslow’s Hierarchy to the next

zone which covers safety needs such as security, employment, and health we

are now at a zone where the necessities of life (food, shelter, warmth) have

been covered, and we are now able to begin investing in our safety and

well-being. Many of these needs can be best met through public provision through

legislation, policing, laws, and our legal system. Thus, the belief is that

since your base needs are met, and some of the next level of needs can be

considered public goods, they can be provided through a tax and re-distribution

system. Thus, if your income rises such that you can begin to concern yourself

with this level, you ought to begin paying a proportion of your income to the

government to provide these services.

As one receives higher and higher incomes that

allow them to devote a smaller proportion of this income to these basic physiological

needs, they have a greater ability (although not necessarily willingness) to

pay into taxation to provide a greater provision to society as a whole.

Along these lines, it has been justified to have

low-income earners pay a small percentage of their total income towards

taxation, and when income increases the proportion, they pay in taxation would

also increase through the marginal tax rate.

Marginal

Propensity to Consume

The other basis for vertical

equity is based on the notion of the marginal propensity to consume (MPC).

While a mouth full, the marginal propensity to consume is a measure of how much

extra money you will spend on consumption for an extra dollar earned.

For example, if you receive an

extra dollar in income and spend 80 cents on consumption (thus saving the other

20 cents) it would be said that you have a marginal propensity to consume of

0.80.

It is typically found that the marginal propensity to

consume is not constant with income. In many ways, this supports the previous

conversation around Maslow’s Hierarchy of needs. It is often found that at the

lower ends of the income spectrum, households will have a marginal propensity to

consume close to, if not equal to 1.00. This means, that for every extra dollar of

income earned, they will spend this entire dollar on consumption. Having been

in this state for many years, I can attest that every dollar has immense value

as it provides extra goods and services which are utilized to meet one’s base

physiological needs of food, clothing and shelter.

However, as one’s income begins to increase, we

find that one’s marginal propensity to consume begins to decrease. That is, as

one has access to more income, they can cover their base

physiological needs, and then have leftover income which they are then able to

save or invest to meet future or other needs.

Robert Reich in his Netflix documentary “Saving

Capitalism” makes the analogy that a person only needs so many pairs of pants, food,

shelter, etc. At lower levels of income, all your resources are going toward obtaining

these basic necessities. As your income rises you may begin to buy more pants,

food, shelter, etc. but at some point, you don’t need another pair

of pants, or another cup of coffee, thus your consumption slows, and this extra

income is moved into savings instead.

Based off of both of these theories, it would

be largely unethical to place a tax burden on those with low incomes as they

may be already struggling to meet their base physiological needs which can be

evidenced by the higher marginal propensity to consume. However, as one’s

income increases, their ability to pay also increases and thus one ought to

increase their contribution to society through taxation.

Of important note – hardly ever does an

increased ability to pay translate to a higher willingness to pay

Further supporting the notion that vertical

equity is preferred in taxation structures is the common desire for a level of

income equality, or more specifically, a low level of income inequality. Thomas

Piketty is one the world's leading economists exploring the role of income inequality

and some of its causes. One of Piketty’s more surprising discoveries is that taxation

systems that are more progressive result in more equal incomes before taxation.

This is surprising, as it was often understood

that a highly progressive taxation structure results in greater income equality

after tax, because the rich are taxed more, with some of this tax being

re-distributed to the bottom. While this is true, the discovery was that highly

progressive taxation structures also result in more equal income distributions before

the taxes are even collected.

I won’t get further into the weeds on this,

other than to say that there is plenty of work done showing the importance of

income equality in promoting social cohesion and stability. Thus, for all the

reasons mentioned above, it is often accepted that a progressive taxation

system that holds to notions of vertical equity is a desired state for a fair

and just tax system. The area of controversy or argument is around how

progressive such a system should be.

Horizontal Equity

I won’t take nearly as long to go

through this term as it is by far less controversial and much better understood.

The notion of horizontal equity

is that those who earn the same income should pay about the same in taxes. That

is all households with an income of $50,000 should pay about the same amount of

taxes for a given system to be fair and just.

Property Taxes

Let’s then attempt to overlay

the above discussion about fair and just taxation to property taxes. To briefly

summarize to start us off, it is argued that a fair and just system of taxation

is a system that appeals to notions of both vertical and horizontal equity,

that is, a system which is progressive as incomes rise, and relatively constant

across similar incomes.

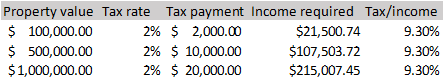

Property taxes however are not

an income tax, but closer to a wealth tax. This is because you are taxed based

on the value of your real estate. The rate at which the value of your real estate is taxed is a flat rate. That is if we suppose a given municipality

had a tax rate of 2%, all property would have to pay 2% of its value in

taxation irrespective of if the property was worth $100,000 or $500,000 or a million

dollars. This can be seen in the table below:

Note,

in reality, property tax rates are typically less than a half percent of the property’s

value, for example in Langford BC the Municipal tax rate was $2.08835 per $1000

of value, or 0.2088%).

Now – to determine if these

property tax rates have a level of vertical equity, we need to attempt to

transition this tax rate from being taxed based on wealth to being taxed based

on income. To do so we must assume that higher incomes can purchase higher-valued homes. If we make a simplifying assumption that the maximum qualified

amount is a payment equal to a third of one’s income we get the following

incomes, and then the following property tax/income rates:

What we witness is that based on

this assumption a flat rate across property values translates to a flat rate to our incomes.

However, it would similarly not

be a stretch to presume that those at lower income levels may be forced to ‘max

out’ their qualification limits to be able to afford shelter, while those at

higher income levels may choose to devote a lower proportion of their income

towards their shelter. The result of this would cause a property taxation

regime to skew towards being regressive as can be seen below:

Note: the assumption is that each income category devotes

33% (1/3), 25% (1/4), and 20% (1/5) of their income to shelter respectively

Thus, our takeaway from this is that, at best,

a property tax scheme is a flat tax rate, and at worst is regressive. Most

likely we are more in the regressive realm than the flat realm. That is,

property tax likely fails at being a fair and just taxation structure as it

fails to achieve vertical equity.

Can we try to make

property taxes more equitable?

If property taxes are by default

likely a regressive form of taxation, there is a natural question that arises.

I)

Can

municipalities change their taxation structure to make this system more

progressive?

There are a few answers to this. The simple

answer is ‘no’. As municipalities are not a level of government defined in the

constitution, they have no prescribed authority to collect taxes beyond the authorities given to them by the

provinces. That is, their ability to raise funds through taxation is strictly

dictated to them by the province. As such, municipalities can

change the rate of taxation but have very little flexibility beyond that.

This however doesn’t mean there is nothing that

can be done to promote a more progressive system. It just means that policymakers need to be a bit more creative, looking at all the social outcomes, not

just the tax incidence.

For example, municipalities do collect revenue

through other sources such as user fees and developer amenity contributions. Focusing

for example on amenity contributions, these funds could be utilized in one of two

ways:

I)

Provide

new community amenities such as green space, parks, community centers, or public

services.

II)

Re-direct

these funds back to the taxpayer in the form of a transfer.

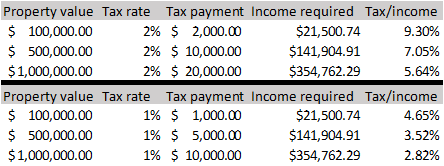

Now in many ways, the economist in me sees tremendous value in option (II). After all individuals have a much better understanding of where a dollar should be spent to give them the best benefit. Unfortunately, given the nature of the municipal tax and transfer system, a transfer back to the taxpayer by cutting tax rates (say we cut by 100bps from 2% to 1%) will disproportionately benefit the taxpayers with the highest value homes, thus doing nothing to promote vertical equity as can be seen in the table below:

Option (I) on the other hand

provides parks, green spaces and public spaces that can be utilized by everyone.

Here is the crux. While everyone benefits from these community spaces being provided,

those at the middle to lower end of the income spectrum tend to benefit disproportionately

from such services.

Why?

One of the biggest arguments put

forward as to why this is the case is that higher value real estate often

includes larger yards, which can be thought of as a private park, or private piece

of green space, while lower value real estate typically has less of a yard if

any.

Thus, while the public provision

of parks and greenspace does positively affect everyone, those without private

yards (lower-valued real estate) are the ones who tend to benefit

disproportionately from such policies.

That is, by engaging in option

(II) one is in many ways adding insult to injury, as by doing so the policymaker is choosing to disproportionately subsidize those who already have highly valued real estate and typically have access to private green space while simultaneously

not providing public green space for the rest of the residents.

Thus, while option (I) will not

necessarily result in lower taxes, and may not necessarily result in a move

towards vertical equity, it does have the potential to increase social welfare

by allowing for a more fair and equitable provision of public amenities

which may greatly increase the welfare of those who are already paying a higher

proportion of their incomes in property taxes.

Summary

Throughout this post we have

introduced the basis of ability to pay, differentiating between income and

wealth. From here we moved on to evaluate flat, progressive and regressive

taxation structures before moving on to look at the notions of vertical and

horizontal equity in an attempt to define a fair and just taxation structure.

We then saw that property taxes fail to achieve vertical equity, and are in

fact typically regressive in nature. Based on this a brief thought experiment

was explored to evaluate whether or not property taxes could be made more

progressive, or at the very least, be utilized in such a way as to improve

social benefit.

Continuing on this theme the next post will be

on the topic of the high cost of low taxes followed by a discussion on user fees, pay-for-access services, and their potential role in

the provision of public goods and services as well as the role they play in tilting

the total taxation system more toward a progressive or regressive one.

If you have any thoughts or comments, please

feel free to comment below.

No comments:

Post a Comment